About Us

Horowhenua 11 (Lake) Block

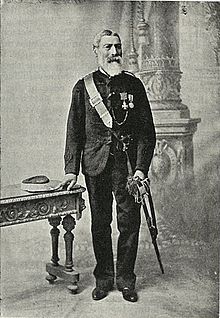

Te Rangihiwinui Kepa was a chief and military

commander of Putiki, Wanganui

The Lake bed and surrounding land is held in trust for the Maori owners who own any part of the Horowhenua 11 Block. The water and surrounds comprise a fishery. The Trust is comprised of eleven (11) elected trustees, as representatives of the Maori beneficial owners. It operates in accordance with a Trust Order put in place by the Maori Land Court on 26 November 2012, and amended on 29 September 2014. The purpose of the Trust is to administer Lake Horowhenua and associated land for the benefit of all Muaūpoko beneficial owners.

“The Lake was included in the land set apart. I intended that 3 chains should be reserved round the Horowhenua Lake, and on both sides of the Hokio Stream down to the sea. … I included Horowhenua Lake in the land for the people for fear it should be drained. It has always been the food-supply of the people, from the time of my ancestors till now, and is highly prized…Those whose kainga are inside the reserve should shift their houses back, and plant trees on the reserve, to beautify it. … I ask the Court to vest the Lake and the reserve round it in a trust, to be chosen by the people.”

Te Rangihiwinui Keepa (Major Kemp), 1896

(The Horowhenua Block: Minutes of proceedings and evidence in the Native Appelate Court under the provisions of “The Horowhenua Block Act, 1986.” [In continuation of G.-2, Sess. II., 1897.] p 146-147)

The Lake Trustees believe that the Lake should be managed in accordance with Muaūpoko tikanga and all decision making surrounding environmental management should remain solely with the Trust as envisaged by Major Kemp in 1896.

Current Trustees

Lake Horowhenua

Lake Horowhenua (the “Lake”) is within the traditional tribal area of Muaūpoko and is a focal point for the iwi. Lake Horowhenua is of immense cultural significance to Muaūpoko and has been a point of contention between Europeans and Muaūpoko since their arrival. Throughout history both groups have attempted to assert complete control over the area and catchment to ensure each of their culture thrives. The disconnect between the drivers of both of these cultures manifests itself strongly in lore and law and the resulting environmental management or kaitiakitanga of the area.

Punahau or Lake Horowhenua has values to Muaūpoko that transcend time and holds the memories and essence of Muaūpoko. The Lake is valued across many dimensions of Muaūpoko culture. Punahau is viewed as the heart of Muaūpoko and connects the people to the land and all its waterways, from Nga Pae Maunga, Tararua through to the Te Tai Hauauru. These waterways or connections also connect Muaūpoko to the sites and places our ancestors such as Kupe, Whatonga, Tara, Haunui-a-naina, Tuteremoana who occupied and completed great deeds of discovery and occupation.

Punahau and its waterways and connections are also of great spiritual significance as the Lake is seen as a connection of water from the underground (Papatūānuku) and the sky (Ranganui) and the resting places of our ancestors in the ranges. The Mauri of our Rohe and people can be monitored and measured based on the health of our Lake. The Wairua of the people is also connected at this point and it is well recognised that if the Lake is not healthy or strong in Mauri then the people will also suffer.

Lake Horowhenua is owned by the Muaūpoko Iwi

The Lake over time has come to mean many things to many people and represents a range of values for different whānau and hapū. Each Muaūpoko, whānau or hapū connects to sites on a physical and spiritual level in many different ways. However, the Lake has primarily sustained Muaūpoko as a place of shelter and a place of sustenance. The Lake has a range of cultural sites associated with it where individuals, whānau and hapū all interacted with it in numerous ways. Each site was managed in accordance with Muaūpoko tikanga and kawa yet maintained by individuals, whanau and hapu for the benefit of Muaūpoko. This concept of kaitiakitanga provided for the maintenance of the kaitiaki or protectors of the Lake and the taonga species that seasonally occupied the Lake, ensuring Muaūpoko tikanga was maintained and in turn also the Mauri of the Lake.

The physical sites of significance around the Lake grew and changed with our changing Iwi. Over time as our Iwi expanded the need for greater resources saw our Iwi develop a series of initiatives such as Island Pa/Pataka, Pa Tuna etc. these sites modified the environment to ensure the survival and expansion of the iwi. These developments also occurred with respect to Muaūpoko-tanga and were implemented and managed in accordance with Muaūpoko tikanga for the benefit of the majority of the Iwi.

While the Lake area contains many wāhi tapu the Lake as a whole has never considered as wāhi tapu. This is because the Lake is far greater and broader than being classified into a specific cultural regime. In and around the Lake margin there are urupa, pa, pa islands and other wāhi tapu that each whanau and hapu connect to and interact with on their own terms.

Trust Lands

In 1898 the Native Land Court awarded the Horowhenua No. 11 Block (13,140 acres) to 82 individual Muaūpoko owners. Lake Horowhenua and the Hokio stream were included in Block 11, but were treated separately, as set out below.

While the balance of Block 11 was awarded to individuals, who were free to subsequently partition out and alienate their individual interests, The Lake bed and a one chain strip surrounding it, and the Hokio stream and a one chain strip running along its northern bank, were vested in 14 trustees, representing the owners of Horowhenua 11. These areas thus remained as a reserve in a form of tribal ownership, and were inalienable.

The Horowhenua Lake Act 1905 declared the Lake, containing some 951 acres, to be a public recreation reserve, to be under the control of a Domain Board. The owners named by the Court in 1898 were also to enjoy ‘free and unrestricted’ use of the Lake and of their fishing rights over the Lake’, subject to recreational use by Levin residents to be regulated by the Domain Board. The 1905 Act also permitted the Crown to acquire a small area adjacent to the Lake as a Domain and a site for boat sheds and other buildings. Successors to the original trustees were appointed by the Maori Land Court in 1951.

Lake Horowhenua (Punahau) in Horowhenua, an area of the southern Manawatu-Wanganui region of New Zealand

The ROLD Act (Reserves and Other Lands Disposal Act), repealed all existing legislation, including the 1905 and 1916 Acts, and confirmed that the bed of the Lake and its islands, the dewatered area (created by drainage operations) and the chain strip around the Lake, and the bed of the Hokio stream and the chain strip on its northern bank, were vested in the trustees appointed in 1951 and their successors (s18(2)(3)). Further sections (18(5) and s18(13)) declared that the surface waters of the Lake, the 14 acres acquired for the domain reserve, and the dewatered margin of the Lake and the chain strip fronting the land acquired for the domain reserve, were vested in the Domain Board under the terms of Part III of the Reserves and Domains Act 1953. The remaining land (including the lake bed) remained vested in, and under the control of, the Lake Trustees. Domain Board control of the Lake waters remained subject to the owner’s fishing rights.

The ROLD Act 1956 therefore applies to

- the surface waters of the Lake, subject to the fishing rights of the owners named by the Court in 1898 and confirmed in 1905;

- the c14 acres acquired in 1907 for a domain reserve and boatshed;

- that part of the dewatered margin of the Lake and the one the chain strip fronting the c14-acre domain reserve.

The ROLD Act does not apply to

- the bed of the Lake;

- that part of dewatered area and chain strip around the Lake not fronting the domain reserve; and

- the bed of the Hokio stream and the chain strip on its northern bank

The ROLD act in combination with many other acts e.g. Maori Fisheries Act 2004, RMA 1991, Conservation Act 1987, Reserves Act 1977, Te Ture Whenua Act 1993 creates a legislation minefield for the management of the Lake and causes great confusion for the beneficiaries and at times the Trustees.

However, the Lake Trustees believe that the Lake should be managed in accordance with Muaūpoko tikanga and all decision making surrounding environmental management should remain solely with the Trust as envisaged by Major Kemp in 1896.

Contact